September 7, 2021

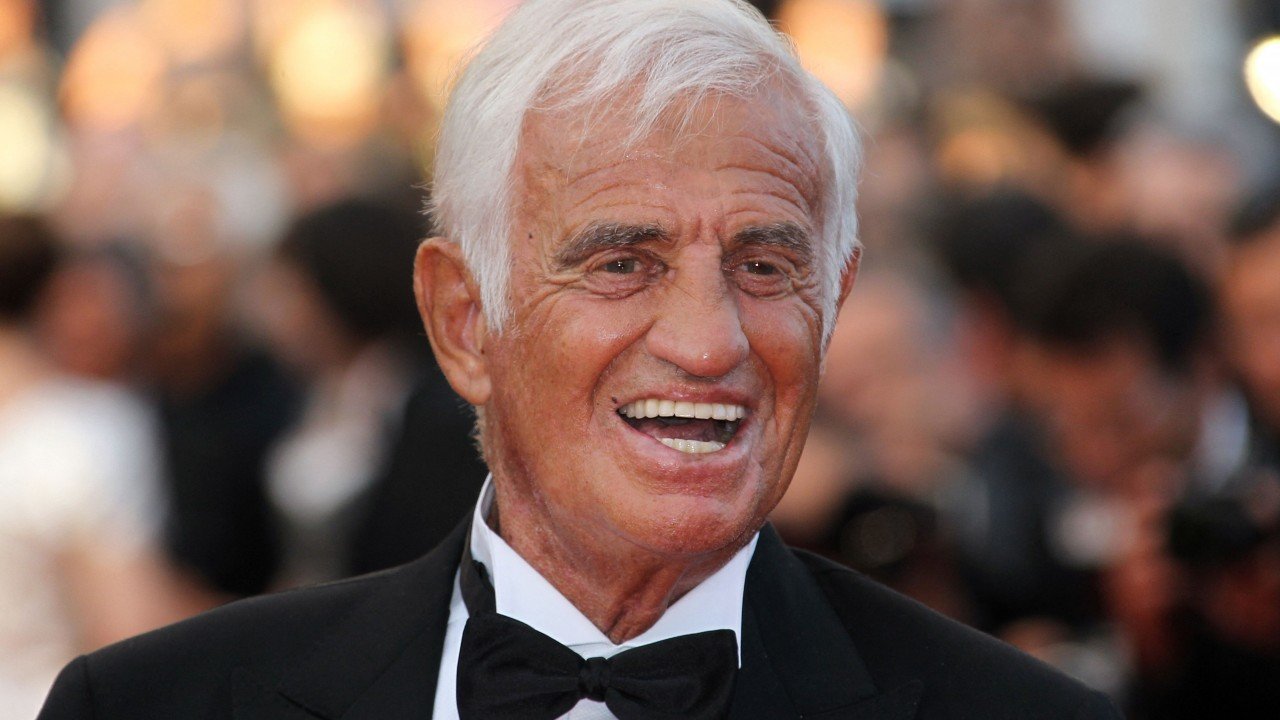

TrueNewsBlog – Jean-Paul Belmondo was born on April 9, 1933, in the middle-class Parisian suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine. His family moved to the city’s Left Bank when he was a boy, and he grew up in the neighborhoods around Montparnasse and Saint-Germain-des-Prés. His father, Paul Belmondo, who was born in Algiers to a family of Italian origin, was a highly regarded sculptor. He later told interviewers that his son had been a tempestuous boy who had gotten into frequent scraps and did poorly in school.

The boy’s mother, Madeline Rainaud-Richard, pushed him to do better, but he resisted, Mr. Belmondo later recalled. Finally, he dropped out of school altogether as a teenager. At 16, he became an enthusiastic amateur boxer (although his famous smashed nose came not from an organized bout but from a playground dust-up), giving it up only when he turned to acting.

“I stopped when the face I saw in the mirror began to change,” he said.

For several years, until he was 20, his parents paid for acting lessons at a private conservatory. After a six-month military tour in Algeria, he returned to Paris in 1953 and was accepted into the Conservatoire National d’Art Dramatique, where he studied for three years. The school, a conservative one, didn’t know what to do with the insolent young man who sauntered onto the stage in a Molière play with his hands in his pockets.

When, at his graduation, in 1956, Mr. Belmondo was awarded only an honorable mention by his teachers, the other students hoisted him on their shoulders and carried him from the theater as he flashed an obscene gesture at the judges.

Jean-Paul Belmondo and Catherine Deneuve.

For all his flamboyance and occasional fistfights, Mr. Belmondo was said to be a consummate professional on the set. Although in later years he continued to work now and then with the great directors of the New Wave — most notably with Truffaut in “Mississippi Mermaid” (1969) — most of his energies went into mainstream favorites. Many of his films after the mid-1960s were made by his own production company.

More and more Mr. Belmondo became known for popular adventures, usually comic thrillers. And he became famous for elaborate stunts in which he took great pride in performing himself. He hung from skyscrapers, leapt across speeding trains, drove cars off hillsides. Co-stars said he seemed all but fearless. While shooting one scene in South America, he was warned that a river, into which he was about to plunge for a scene, was filled with poisonous snakes and piranha. Mr. Belmondo grabbed a chunk of corned beef and slung it into the murky water. When nothing happened, he jumped in and filmed the scene.

He said he had decided, “What the hell, if they’re not going to chew on that, they’re not going to eat me.”

Finally, an injury during the filming of “Hold-Up” in 1985, when he was 52, forced him to leave the stunts to the stunt men.

Hollywood Was Not for Him

Throughout, the Belmondo cult endured, though more in France than around the world. His French fans knew him by his nickname, Bébel (pronounced bay-BELL).

No matter the scene, no matter the co-stars, whatever mayhem was breaking out onscreen, Mr. Belmondo was always able to affect a calm, cool remove, as though he was more amused than aroused by the activity swirling around him. He brought a touch of comedy to his action roles and a hint of danger to his comic roles; one could well imagine him playing the reluctant, wisecracking hero in American action series of the 1980s like “Die Hard.”

Mr. Belmondo never made the transition to Hollywood, largely because he didn’t want to. “Why complicate my life?” he said. “I am too stupid to learn the language and it would only be a disaster.”

In 1989 he was awarded the Cesar Award for best actor, the French equivalent of the Oscar, for his performance in Claude Lelouch’s “Itinéraire d’un enfant gâté,” playing a middle-aged industrialist who fakes his death and then sails the world.

By this time he had slowed his frenetic pace, making only nine movies in the 1980s, compared to 41 in 1960s and 16 in the 1970s. He cut back even more in the ’90s, when he made only six films, but this was due in part to a belated career shift. Mr. Belmondo had not appeared in a live production since 1959 when he returned to the theater in 1987. Particularly well-regarded was his sold-out run as “Cyrano de Bergerac” in Paris in 1990.

A stroke in 2001, however, forced him to stop working. Not until eight years later was he back before the cameras, shooting “Un homme et son chien” (“A Man and His Dog).” Released in 2009, it tells the story of an older gentleman who, accompanied by his loyal dog, suddenly finds himself without a home.

Late in life, when he was a little thicker and much grayer, Mr. Belmondo liked to affect some of the self-effacing modesty that was noticeably absent when he was at his peak in the 1960s.

When an interviewers asked him to explain his enduring popularity, especially with women, Mr. Belmondo responded with his usual casual shrug.

“Hell, everyone knows that an ugly guy with a good line gets the chicks,” he said.

Story first published by the New York Times.