|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: NATHANIEL BALLANTYNE

TRUENEWSBLOG- The American government has a team on the ground in Haiti working with the American Embassy and the local authorities to recover a group of kidnapped missionaries and their children, White House and law-enforcement officials said Monday.

“The president has been briefed and is receiving regular updates on what the State Department and the F.B.I. are doing to bring these individuals home safely,” Jen Psaki, the White House press secretary, said at a news briefing. “We can confirm their engagement, and the U.S. Embassy in Port-au-Prince is coordinating with local authorities and providing assistance to the families to resolve the situation.”

The brazen attack, in which a Haitian gang captured 16 Americans and one Canadian working with the Ohio-based Christian Aid Ministries, is the most recent example of the lack of security in Haiti, where many feel violence and crime have spiraled out of control.

On Monday, some Haitians took to the streets to demand that it be stopped.

Small, peaceful protests erupted across the country, with groups in at least eight towns and cities demanding a government response. Some burned tires and blocked roads with barricades. Many stores in the capital, Port-au-Prince, were closed, including gas stations, part of a general strike aimed at forcing the government crack down on the increasingly powerful gangs.

In Port-au-Prince and in other areas, streets were empty, with small groups patrolling intersections, tending to the flames of burning tires.

Calls for a broad strike had emerged last week, as the desperation of Haitians in the face of mounting lawlessness tipped into anger. But Saturday’s kidnapping of the missionary group, which included five children, added to the tense atmosphere and underscored the misery of everyday Haitians.

The group is believed to have been taken by the 400 Mawozo gang, a growing menace in Port-au-Prince. The gang has increased its territorial control over the past year, while the government struggled to cope in the face of natural disasters and the assassination of the country’s president in July. The killing remains unsolved.

The presence of other gangs grew during the last year as well. By many estimates, about half of the capital is under the command of armed criminal groups, many of which use kidnappings to raise money, sparing no one, not even children, priests or the poor.

The 400 Mawozo gang introduced a new type of kidnapping to Haiti this year: abductions en masse, where entire buses are taken hostage until the families of passengers can pay ransom.

The gang’s growing control has left one suburb, Croix-des-Bouquet, a near ghost town. Many families gave up their homes to seek more stable lives, hoping to once again be able to do basic things like walk down the street or send children to school without fear.

Highlighting how much the government has lost control of security, Prime Minister Ariel Henry’s convoy was shot at on Sunday as he traveled to lay a wreath at a statue of one of Haiti’s founding fathers in downtown Port-au-Prince, to commemorate his assassination.

Hours later, Jimmy Chérizier, an infamous gang leader known as Barbecue, led a large procession through the capital to place flowers at the same statue that had been out of the prime minister’s reach.

The audacity of the gangs and the police’s inability to contain them have rekindled discussion about the possibility of deploying police and security officers from other countries, perhaps under the authority of the United Nations or a regional group like the Caribbean Community, known as Caricom.

But many Haitians remain opposed to such outside intervention, seeing it as an affront to their country’s sovereignty.

They are also embittered about the legacy of foreign interventions, particularly of the United Nations peacekeeping mission that was deployed in Haiti before, during and after the 2010 earthquake. A Nepalese contingent of that force introduced a devastating cholera epidemic to Haiti, and the United Nations never provided compensation to the victims and their families.

Three Recent Crises Gripping Haiti

The abduction of U.S. missionaries. Seventeen people, including five children, associated with an American Christian aid group were kidnapped on Oct. 16 by a Haitian gang as they visited an orphanage. The brazenness of the abductions has shocked officials. The whereabouts and identities of the hostages remain unknown.

The aftermath of a deadly earthquake. On Aug. 14, a 7.2 magnitude earthquake struck Haiti, killing more than 2,100 people and leaving thousands injured. A severe storm — Grace, then a tropical depression — drenched the nation with heavy rain days later, delaying the recovery. Many survivors said they expected no help from officials.

The assassination of President Jovenel Moïse. A group of assailants stormed Mr. Moïse’s residence on July 7, killing him and wounding his wife in what officials called a well-planned operation. The plot left a political void that has deepened the nation’s turmoil as the investigation continues. Elections that were planned for this year are likely to be delayed until 2022.

Many Haitians also harbor resentment over the failure of a peacekeeping mission, known by its French acronym, Minustah, to make their country safer and more stable before its mandate ended more than three years ago.

“The vast majority of Haitians don’t like foreign military intrusions, especially given the failed intervention of the U.N.,” said Robert Fatton Jr., a professor in the Department of Politics at the University of Virginiawho was born and raised in Haiti and has written several books about the country. “When they left there was nothing.”

On the other hand, Mr. Fatton said, “the police in Haiti are completely dysfunctional now — the gangs have taken over Port-au-Prince, and they are probably better equipped than the police.”

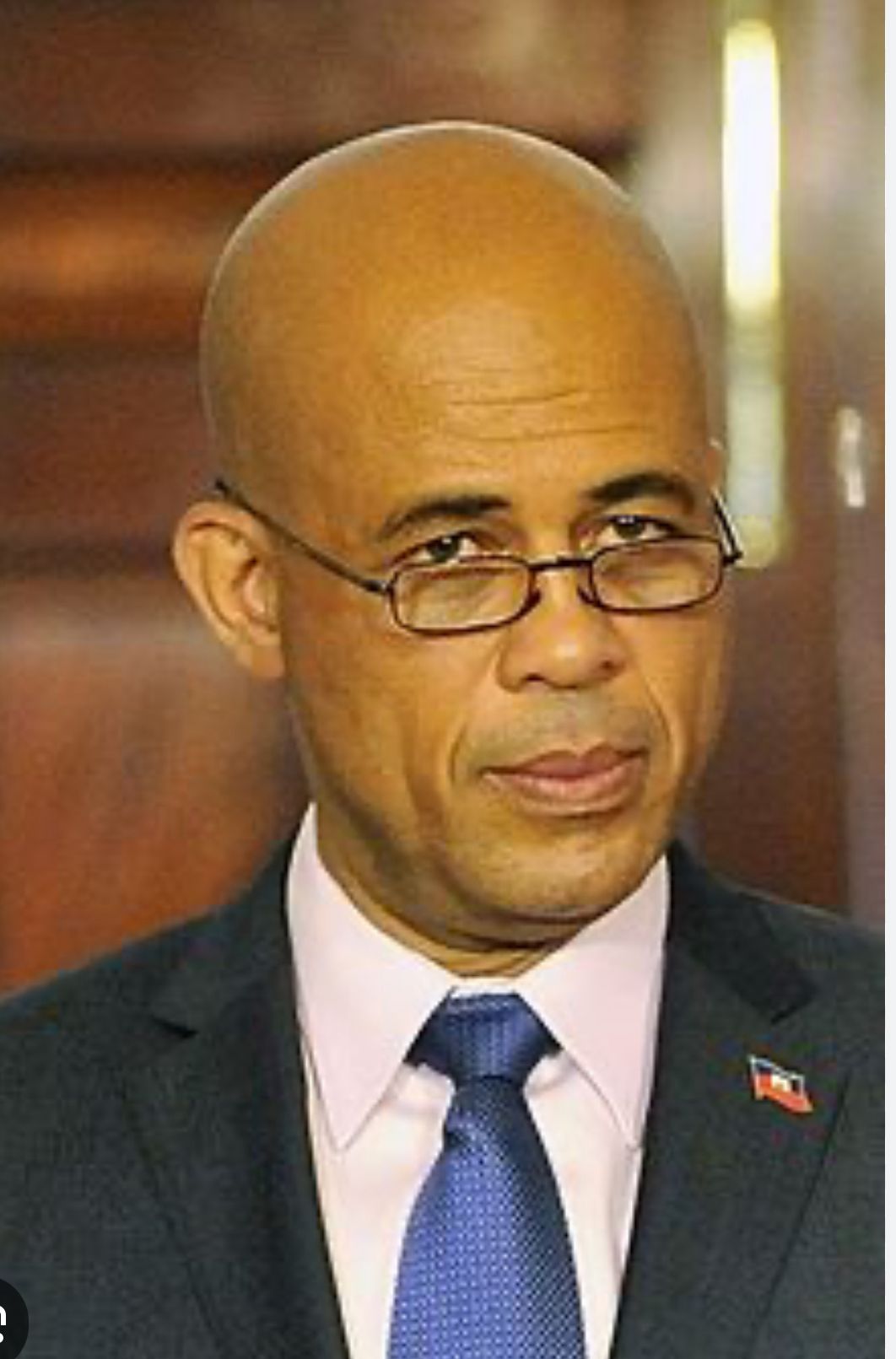

Laurent Lamothe, a former prime minister of Haiti, told CNN in an interview Monday that “the spiral of violence is unprecedented.”

When the U.N.’s peacekeeping mission left in 2018, Mr. Lamothe said, it left a “huge security void,” with a police force not capable of fighting the gangs or bringing Haiti under control. He said the Biden administration should “reinforce the Haiti national police with supplies and equipment.”

A successor mission to Minustah, known as the United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti, has no peacekeeping or security role. Its purpose is primarily to provide guidance to the Haitian authorities, including on ways to improve political stability in the country. Its mandate, which was to expire on Friday, was extended until July by the United Nations Security Council.

Asked about the Saturday kidnapping, Stéphane Dujarric, a spokesman for Secretary General António Guterres, told reporters on Monday that he was “very concerned about what we’re seeing, about the dramatic deterioration of the security situation, which includes these rampant kidnappings.”

Mr. Dujarric did not specify whether Mr. Guterres wanted to see resumed United Nations peacekeeping operations in Haiti, a decision that only the Security Council can make, but he said that the United Nations would continue “to work with Haitian authorities to strengthen Haiti’s democratic institutions and public order.”