March 13, 2021

Coronavirus- Covid-19 – Federal Prison-Fort Dix.

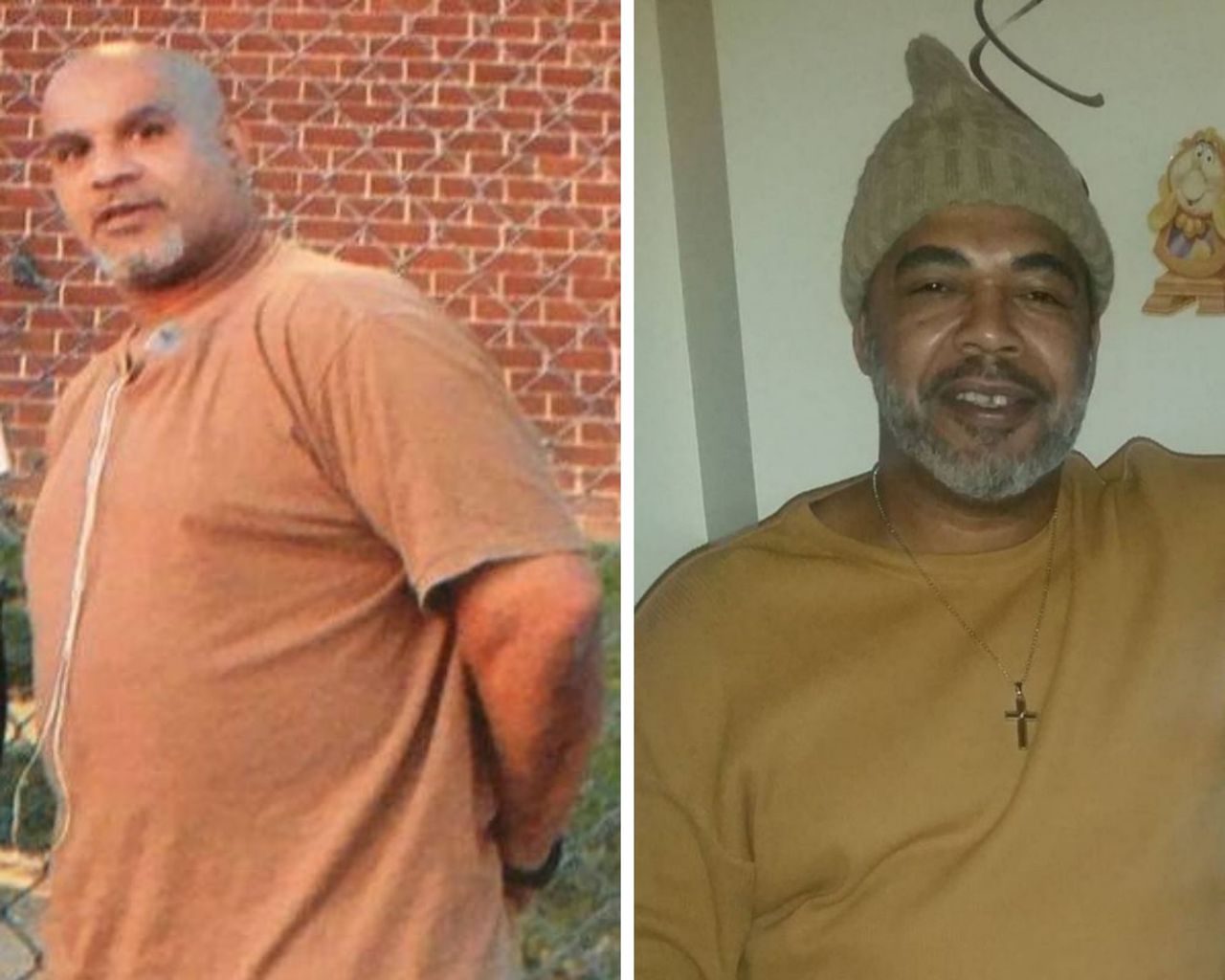

TRUENEWSBLOG- Dominick Pugliese and Myron Crosby both contracted COVID-19 while incarcerated at Fort Dix federal prison and later died from complications of the virus.

When a federal judge released Dominick Pugliese from custody in February, the former Fort Dix inmate was nearly dead.

It was the exact dire situation Pugliese feared could happen when he applied for compassionate release last April as the coronavirus pandemic began devastating the region.

Pugliese told prosecutors and a federal judge that the virus could place him in greater danger of having a serious illness due to his underlying health conditions, like asthma and hypertension, according to court documents.

Prosecutors, according to court documents, opposed the release of the man sentenced to nearly 20 years in 2016 on drug trafficking and firearms charges, saying he had not served sufficient time, while also questioning the seriousness of his medical issues.

Pugliese’s petitions to be released were dismissed multiple times by a judge, according to court documents.

Then it happened. Pugliese became one of nearly 2,000 inmates at the federal prison in Burlington County to contract the virus — the highest number of cases of any federal correctional facility, according to the Bureau of Prisons.

It is unclear when exactly he tested positive, but his family claims it happened sometime after he was moved from a two-man prison cell to a room with 11 other inmates, as outbreaks infected every corner of the prison. On Jan. 7, according to court documents, a chaplain had reached out to Pugliese’s daughter to let her know her father had contracted COVID-19 and was being treated at a local hospital.

The family says it was told nothing else.

Over the next month, prison officials declined to alert Pugliese’s family or his public defender to how he was doing or where the Pennsylvania native was being treated out of security concerns.

They would later learn that Pugliese was suffering from “severe COVID pneumonia,” according to a court document filed by his attorney in February, and that Pugliese had been in the intensive care unit for more than a month and was now on a ventilator.

By mid-February, Pugilese could no longer respond to verbal or tactile stimuli, and medical staff described his condition as “‘extremely grave,’ with a 78% likelihood of mortality,” wrote Quin Sorenson, the attorney.

“The defendant, Dominick Pugliese, is dying,” Sorenson wrote to a judge on Feb. 12 as he sought to have Pugliese released from custody. A federal judge agreed to the release that day.

“The Court does not find the ends of justice would be served by keeping Defendant in custody and denying his family access to his whereabouts while he undergoes serious illness,” U.S. District Judge Yvette Kane wrote. “The severity of his condition suggests that at best he may be facing prolonged hospitalization and rehabilitation.”

Pugliese was not that lucky.

He died from complications of the virus last week, his family said. The father of six was 61 years old.

Dominick Pugliese pictured with one of his 11 grandchildren. He died from complications of COVID-19 on March 6.

“I am extremely hurt,” said Yvette Moore, Pugliese’s niece. “It could have been avoided if they had some compassion of the situation. It is not like they didn’t know (about his health conditions). Maybe he would still be here.”

“I cry every day,” added Michael Stewart, his nephew. Pugliese’s death is the latest COVID-19 horror story to come out of the Fort Dix correctional institution, where more than two-thirds of the inmate population has contracted the virus during the pandemic, despite officials routinely downplaying the threat of infection in the prison.

By mid-February, Pugilese could no longer respond to verbal or tactile stimuli, and medical staff described his condition as “‘extremely grave,’ with a 78% likelihood of mortality,” wrote Quin Sorenson, the attorney.

“The defendant, Dominick Pugliese, is dying,” Sorenson wrote to a judge on Feb. 12 as he sought to have Pugliese released from custody. A federal judge agreed to the release that day.

“The Court does not find the ends of justice would be served by keeping Defendant in custody and denying his family access to his whereabouts while he undergoes serious illness,” U.S. District Judge Yvette Kane wrote. “The severity of his condition suggests that at best he may be facing prolonged hospitalization and rehabilitation.”

Pugliese was not that lucky.

He died from complications of the virus last week, his family said. The father of six was 61 years old.

“I am extremely hurt,” said Yvette Moore, Pugliese’s niece. “It could have been avoided if they had some compassion of the situation. It is not like they didn’t know (about his health conditions). Maybe he would still be here.” “I cry every day,” added Michael Stew

Pugliese’s death is the latest COVID-19 horror story to come out of the Fort Dix correctional institution, where more than two-thirds of the inmate population has contracted the virus during the pandemic, despite officials routinely downplaying the threat of infection in the prison.

“The Bureau of Prisons (BOP) has taken swift and effective action in response to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and has emerged as a correctional leader in the pandemic,” a BOP spokesman said this week in a statement. “The BOP, including FCI Fort Dix, has instituted a comprehensive management approach that includes screening, testing, appropriate treatment, prevention, education, and infection control measures.”

But inmates have painted a different, much grimmer picture of life at Fort Dix during the pandemic. Dozens of Fort Dix inmates have sought to be released due to the threat of the coronavirus, though the majority have been denied, a fate inmates across the country are also overwhelmingly facing.

Pugliese’s death has eerily similar characteristics to the only Fort Dix inmate to die from the virus while in custodyat the federal prison.

Myron Crosby, 58, had a documented history of a number of health issues including diabetes, a prior heart attack while in custody, obesity, high blood pressure and kidney failure, but like Pugliese, his request to be released on home confinement was denied. He was in the midst of a 14-year sentence for drug distribution.

Instead, Crosby was moved to Fort Dix’s prison camp in the fall, a low-security section of the prison where more than 150 inmates live closely in a dormitory setting.

There, he contracted COVID-19 and soon suffered the worst of the virus, though his family was unaware.

After talking to her father by phone while she was at the hair salon on Jan. 6, Shamelia Crosby never heard from him again.

She and her other siblings constantly called the prison, hoping to get an update on their father. She described it as a game of “telephone tag.” “Where’s my dad?” Shamelia Crosby wondered.

“It was hard,” she said about being left in the dark. “It was frightening. I was nervous. We didn’t know what was going on. I was sick to my stomach.”

No one told them where their father was until Jan. 21 when a chaplain called around 9 p.m. to say Crosby was in the hospital, she said. The next day around 10 a.m., a call came in that her father’s health was rapidly declining. At 12:14 p.m., she was told he went into cardiac arrest. Shamelia Crosby begged them to save her father. He was dead within the hour.

“It spiraled out of control so fast,” she said. “No one was able to say goodbye.”

However, it was only after his death that the Crosby family learned through a Bureau of Prisons press release announcing his death that Crosby had been in the hospital since Jan. 7.

Her family didn’t know he was there until two weeks later, Shamelia Crosby said.

“Instead of being able to comfort our Myron while he was alone in the hospital, on a ventilator, and painfully declining, our family spent weeks trying to learn anything that we could about his status,” the family said in a statement after his death. “We did not hear anything from Fort Dix or the BOP until 12 hours before he died. Myron suffered for weeks by himself in the hospital and then died in the presence of strangers, unable to say goodbye to the family he had talked to every day.”

After his death, Crosby’s family urged the BOP and the courts to release more inmates who are at high-risk, and to treat the inmates and their families with “more compassion.”

“No one should have to go through what we have been through,” the family said.

A BOP spokesman said it is agency policy that if an inmate becomes seriously ill, the institution will “notify the next of kin promptly,” though families in both these instances claim that did not happen.

“They shouldn’t keep people in fear of what is going on with their loved ones, especially when they see us constantly calling,” Shamelia Crosby said. “They were aware.”

As Crosby was dying from the virus, Pugliese’s family was scrambling to locate their loved one and find out how he was doing. By the time they found him, Pugliese was debilitated.

His children visited him at a New Jersey hospital on Saturday before he was taken off the ventilator. It was the first time any family saw him since they first learned he was positive with COVID-19. None of them heard him speak in his final weeks alive.

Pugliese’s children declined to comment as they continue to grieve their father’s death.

“Everyone is going through a grieving point and their main focus is to put him to rest at this point,” Stewart said.

(Source – By Joe Atmonavage | NJ Advance Media for NJ.com).